Five Ways Someone Can Have Autistic Traits, But Not Actually Be Autistic

— Person on Quora

Autism vs. Autistic Traits

How can someone have autistic traits, but not be autistic?

To better understand such a person, we have to differentiate between the sort of brain and behavior a person has (their “neurotype”) and their diagnosis.

“Autism” is a condition defined by the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Disorders (currently on its 5th edition).

“Autism” includes people with a lot of different neurotypes. That’s why they say “when you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.” Some autistic people are genius writers and public speakers, while others can only say a few words. Some do well in school and others don’t. Some are hypersensitive to taste and are picky eaters, while others are hyposensitive and will eat pretty much anything, the stronger the better.

So, “autism” doesn’t mean a particular kind of brain. It’s more like a family of people who have some traits in common.

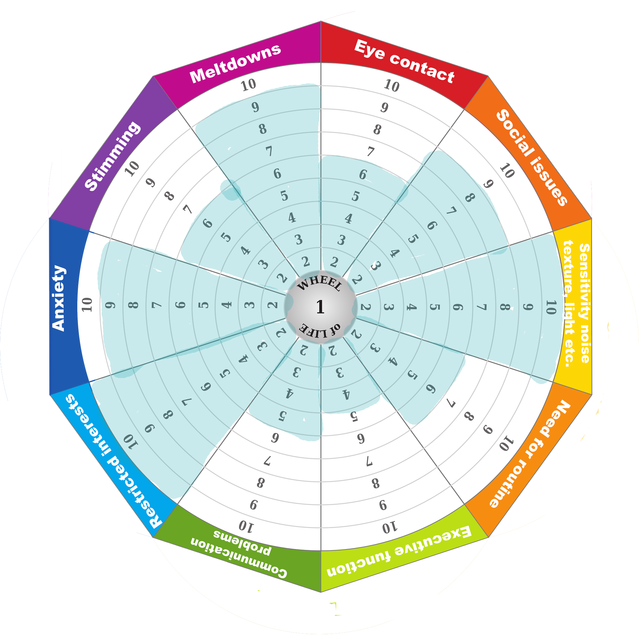

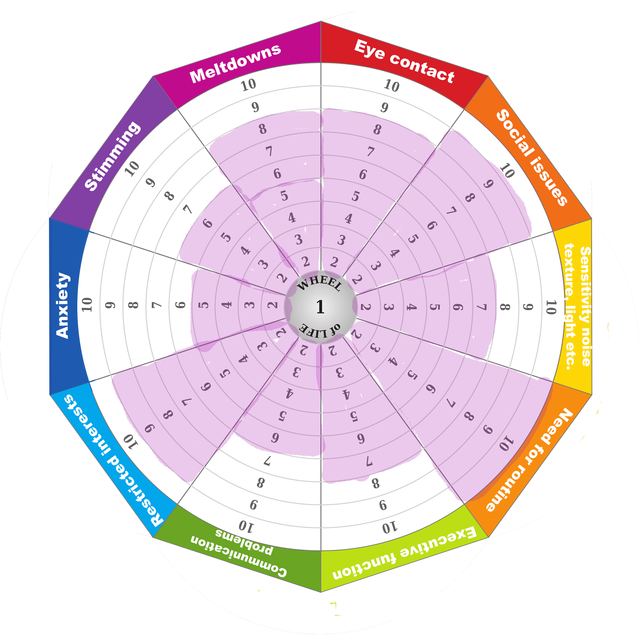

For example, the two people represented by the blue and pink wheels below are similar in some ways, because they are both part of the “autism” family. But their distribution of traits is different, so they look and act differently.

Now let’s look at what “autistic” traits are…and how someone can have these traits but not autism.

One: Not Enough Social Traits

Meet Abby. Abby is six years old and in first grade. Her teachers are worried she isn’t making friends at school, and her parents were already concerned. She has just been taken for an autism evaluation.

The DSM-5 says: “a person must have all 3 persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, currently or by history,” including:

1. Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions.

Abby does not know how to approach other children to interact. She waits for them to come to her. She can talk, but she does not know how to have a back and forth conversation. She doesn’t talk much, except when someone brings up her intense interest in horses — then a torrent of words comes pouring out of her. When she interacts with people, her emotions don’t show much on her face. Abby has this trait.

2. Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication.

Abby does not make much eye contact and looks at people from out of the corners of her eyes. Her gestures are not well timed with her speech. As mentioned previously, she does not show her emotions on her face or body language very much. People can find it hard to tell what she’s feeling. Abby has this trait.

3. Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers.

Abby does not adjust her behavior to suit different social contexts much. However, she often plays pretend with her sister. She watches other children with interest. When people start a conversation with her, she talks a lot, and when people start a game with her, she responds. Even though she does not know how to approach other people or hold a conversation, she clearly shows her interest in other people. Abby does not have this trait.

Abby has only two out of three social traits. It doesn’t matter how strongly and obviously she might have those two traits, it matters how many traits she has. She doesn’t have enough social traits to be autistic. She will not be diagnosed with autism.

Two: Not Enough Restricted, Repetitive Patterns of Behavior

Meet Ben. Ben is 12 years old and in 7th grade. He is extremely anxious. He gets good grades and tests as having above average IQ. He has an excellent memory and can tell you all sorts of obscure facts about his interests.

To be autistic, Ben needs to “manifest…at least two of the following, currently or by history”:

1. Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypes, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

Ben has never shown any obvious stereotyped movements. Like his more neurotypical siblings, he bites his nails when anxious. He does not have this trait.

2. Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat same food every day).

Ben likes to eat the same breakfast every day, and sit in the same chair at the dining room table. However, he does not seem particularly distressed by changes to his routines. He does not have this trait.

3. Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g., strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests).

This is one of the more common traits a non-autistic person might have. For his whole life, Ben has gone through a series of extremely focused interests that last anywhere from 3 months to a year at a time. These have become more “typical” over time and have included cars and trucks, dinosaurs, and Nintendo video games, and currently, Dungeons and Dragons. He always wants to talk about, play with, or learn about these interests and quickly gets bored by other topics. Ben has this trait.

4. Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g. apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement).

This is the other trait that is very common for a non-autistic person to have. Ben does not show any unusual responses to sensory input in his environment. He does not have this trait. (His younger sister, on the other hand, is fascinated by twinkling lights, and yells when someone sings off key or when people bang pots and pans in the kitchen).

Ben only has one restricted/repetitive pattern of behavior, interest, and activities. That’s not enough for a diagnosis of autism. People who see his obsessive levels of interest in his favorite topics sometimes ask whether he is autistic, but he is not.

Three: A Late Start

Cassie is thirty five years old and is burning out at work. She finds social interactions confusing and exhausting, and feels like she has to put up a “mask” to ensure that her behavior is socially acceptable. She only has two friends, and mostly speaks with them online. She has gone through a lot more jobs than her peers with similar amounts of education. She has read about autism recently and thought it sounded a lot like her, and she sought an evaluation.

An autistic person must have diagnostic traits “present in the early developmental period,” even if they only become fully manifest later in life when “social demands exceed limited capacities.”

Cassie did not have the self awareness as a child to know how she compared to her peers early on. She does not remember being particularly lonely or being bullied a lot when she was very small; she grew up in a small, tightly-knit neighborhood and church.

Unfortunately, her parents were not attentive and observant. Cassie was raised by a single mother who worked most of the time. She spent a lot of her time with extended family, who did not know much about child development. Her family have been hard to reach, and they don’t remember much about Cassie’s childhood. They don’t recall her having autism “symptoms” as a small child, but she may have been developing atypically. It’s clear that even if she’d had mild autistic traits, her overworked family wouldn’t have noticed or understood what it meant.

Cassie is not diagnosed as autistic. She is probably some sort of neurodivergent, but there’s not quite enough information to tell exactly what kind. She does seem to have autism traits, and she finds it helpful to join groups for autistic people and allies.

One does not need to be 100% autistic to benefit from learning about autism and participating in autistic communities.

Four: “Insufficient” Impairment

Meet David. David is 42 years old, a serial entrepreneur, and divorced. If you asked anyone to describe him, they would say, “chaotic.” With a lack of tact and executive function difficulties, he’s spent his adult life lurching from one near-disaster to the next, but he’s kept afloat with intelligence, skills, a quick wit, and drive to succeed. Now, though, he’s tired all the time and losing motivation fast. He doesn’t feel depressed, exactly, but everything exhausts him and he doesn’t feel like getting out of bed most days. He doesn’t realize that basic life tasks are harder for him than most people. He thinks things are just as hard for everyone else, his ex-wife was “nitpicky,” and his coworkers and bosses were intolerant and uncreative.

David has a lot of social and restrictive/repetitive traits. But is he autistic?

A person’s “symptoms” need to be judged to “cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning.” If a person compensates well enough that they function fine with family, friends, and on the job — they’re just tired all the time — they might be judged to function well enough. They might still have difficulty with the same things autistic people do — just not enough to be diagnosed.

That’s what happened to David. He lives in a no man’s land where he is close enough to autistic to have difficulties in work and relationships, but not enough to get a diagnosis or accommodations that could help him.

Five: General Developmental Delay

Meet Emma. She is 22 years old and has an IQ of 40. She lives in a group home for young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD, or what they call “learning disabilities” in the UK). She has all the social traits, most obviously difficulty making friends and holding conversations. She has three of the restricted/repetitive behavior traits, most noticeably flapping her hands, stimming by making sounds, and an extremely keen sense of touch and smell.

Emma has all the traits of an autistic person, so she must be autistic, right?

No. A person’s traits must not be “better explained by intellectual disability or global developmental delay…social communication should be below that expected for general developmental level.”

In other words, Emma has a low IQ and has developmental delays in most areas. So, psychologists assumed that her social difficulties and repetitive behavior are “what you might expect from a person with a developmental delay.” So, Emma thinks and acts like an autistic person, but does not qualify.

Why are So Many People Almost Autistic?

How can so many people think and act like autistic people, yet not count as autistic?

This situation is guaranteed to happen any time you apply a binary (yes/no) category to continuous human traits. The cutoff between “autistic” and “not autistic” is always going to be arbitrary, no matter where you put it. The people on other side of the line will always be more similar to each other than different.

It’s like trying to set a dividing line between yellow and green. There are some colors that are clearly yellow, and others that are clearly green. But in the middle of the continuum, there are colors that could be called either, depending on where you place the line. “Just barely green” and “just barely yellow” look almost the same as each other.

But “yellow” and “green” are useful, meaningful categories, and we have to draw the line somewhere.

Arguably, the same could be said of “autistic” and “not autistic.”

Do you think these are useful, meaningful categories? Where would you draw the line? How would you define autism? Comment with these or any other related thoughts you want to share!